by present and past LSSA Presidents Sonja Shield, Jim Provost, and Gibb Surette

Legal Services Workers Organize

In 1972, Legal Services workers in New York City organized themselves as the Legal Services Staff Association. LSSA was determined from the very beginning to be a “wall to wall” union, with every union worker in every legal services office in the city belonging to the same local, regardless of job description. LSSA was one of the very first unions to be organized in the legal profession, which had previously been thought to be virtually unorganizable. LSSA immediately began helping to unionize legal services workers around the country.

First Strike

First Strike

In 1977, the new union saw its first strike. Management scoffed at the union’s contract demands and refused to take the union seriously. When the workers went out on strike, management was so taken aback that the strike resulted in a virtually total victory in little more than a week. LSSA president Jim Braude told the New York Times that “We wanted significant across-the-board increases for our legal workers and parity with Legal Aid Salaries for our attorneys. We got both.” This quick win may have fostered some unrealistic expectations about how easily future strikes could be won, but it gave a tremendous boost to union morale—not only in New York, but across the country, where workers in other legal services offices were attempting to unionize. Among the union’s important gains was a contract provision staying any contested change in work rules until decided at arbitration.

Creating a Nationwide Union

That same year, 1977, LSSA members, who had began to take a central role in supporting the organization of other programs and coordinating communication among legal services unionists throughout the country, organized a conference in New York City. Representatives from some thirty programs, about half of them unionized, came to discuss mutual support and action. The resulting coalition continued to be coordinated from the LSSA office in New York City.  In 1978, the National Organization of Legal Services Workers (NOLSW) was formally founded at a convention in Detroit. It now represents about 4,000 members, in over 110 non-profits, including about half of the Legal Services workers in the country as well as employees of other nonprofits like Heartland Alliance in Chicago. Its members in New York City include LSSA as well as advocates at the Center for Constitutional Rights, Latino Justice, and the Urban Justice Center. The president of LSSA, Jim Braude, was elected the first president of NOLSW. He held that office until 1985, when he was succeeded by another former LSSA president, Dwight Loines. In 2000, Dwight became political director of the UAW’s Region 9A, which includes New York, and the presidency of NOLSW was taken over by Ellen Wallace from Boston. LSSA is still the largest unit within NOLSW, shares offices with the national organization, and continues to play an especially active role in NOLSW activities.

In 1978, the National Organization of Legal Services Workers (NOLSW) was formally founded at a convention in Detroit. It now represents about 4,000 members, in over 110 non-profits, including about half of the Legal Services workers in the country as well as employees of other nonprofits like Heartland Alliance in Chicago. Its members in New York City include LSSA as well as advocates at the Center for Constitutional Rights, Latino Justice, and the Urban Justice Center. The president of LSSA, Jim Braude, was elected the first president of NOLSW. He held that office until 1985, when he was succeeded by another former LSSA president, Dwight Loines. In 2000, Dwight became political director of the UAW’s Region 9A, which includes New York, and the presidency of NOLSW was taken over by Ellen Wallace from Boston. LSSA is still the largest unit within NOLSW, shares offices with the national organization, and continues to play an especially active role in NOLSW activities.

Our First Political Battle

In 1978, the LSC had introduced a reporting system requiring that extensive identifying information about each client be turned over to the LSC, which has no attorney-client privilege. Refusal to comply by an LSSA member in Harlem developed into NOLSW’s first nationwide campaign, and the reporting system was defeated. Such struggles on behalf of the clients and the programs, were to become a regular feature of NOLSW and LSSA activity.

Insisting on a Neighborhood Presence

Management has periodically over the years decided it should close neighborhood offices and consolidate services into fewer offices. The union has typically fought these moves, insisting that New York City residents deserve quality legal services in their neighborhoods. Resisting management’s 1979 push to consolidate borough offices, MFY staff member Bob Hartman told a newspaper “If legal services is worth anything at all, it’s worth it on a storefront basis… You get a feel for the neighborhood, for the problems on the street. You listen to the same complaints, you see the same faces in court, and you know something is going on. You can’t pick that up at Broadway and Worth. It might be a new wave, that everyone in legal services will be in big shiny office buildings and you won’t get a feel for what’s going on out there… In my opinion, the people who are making these decisions don’t know anything about legal services.”

Second Strike

On November 14, 1979, LSSA’s second strike began against new work rules imposed by Executive Director Kathy Mitchell. Management sought to make an example out of LSSA, which was playing a key role in the dramatic nationwide growth of unionization within the Legal Services community. The strike lasted 11 weeks during the depths of winter. LSSA in those days had no strike fund and no hardship fund. Our only affiliation was to the nascent NOLSW, and it had very few resources to share. One of the main issues was seeking strict adherence to affirmative action goals. In the end, the union compromised on the implementation of new work rules, but defeated other giveback demands, won retirement benefits for the first time, added an affirmative action policy, expanded due process rights on the job, particularly for probationary employees, succeeded in getting two staff attorneys who had been fired prior to negotiations rehired, and made modest salary gains. (24% raises!) Best of all, Mitchell and her anti-union offensive were discredited, and she was dismissed. For years thereafter, her successor, Dale Johnson, always came to the table eager to point out first of all that he was not seeking give-backs.

Joining the UAW

By 1979, there was also a growing understanding that connection to a larger organization would enable us to speak with more authority not only to management but to lawmakers. We sought a larger union that was widely recognized as democratically run, politically progressive, innovative and militant, and one that would accept affiliation while respecting a large degree of autonomy at the same time, in deference to the unique character of a legal workers’ union and its issues.  In 1980 NOLSW voted to affiliate with District 65, a diversified union originally organized during the thirties among the warehouse workers, stock clerks, and goods handlers of New York’s garment industry. District 65 was among the few unions to defy McCarthy’s committee, and among labor’s most outspoken supporters of the civil rights movement. Martin Luther King, Jr. called District 65 “the conscience of the American labor movement” because of its consistent commitment to progressive causes. At the same time, District 65 itself was in the process of affiliating with the United Auto Workers (UAW). The eventual bankruptcy of District 65 in the mid-1990’s resulted in NOLSW becoming a direct part of the UAW as Local 2320. The UAW was one of the pioneers of the “wall-to-wall” unionism so central to LSSA. Among the UAW’s other claims to fame is the invention of the sit-down strike (Flint Michigan, 1948). The UAW’s concerns with autonomy and progressive politics led the union to withdraw from the AFL-CIO for several of that coalition’s most conservative years, but it later reaffiliated. Even more than District 65, the UAW proved from the beginning a devoted and invaluable ally in our political battles, including the fight to save Legal Services from defunding. The eventual bankruptcy of District 65 in the mid 1990’s—in large part due to the failure of membership numbers and employer contributions to keep pace with the cost of defined pension benefits for an aging membership—resulted in NOLSW becoming a direct part of the UAW as Local 2320. NOLSW was allowed to continue as a nationwide organization, one of only two UAW locals accorded that privilege. LSSA became the New York City “unit” of UAW Local 2320.

In 1980 NOLSW voted to affiliate with District 65, a diversified union originally organized during the thirties among the warehouse workers, stock clerks, and goods handlers of New York’s garment industry. District 65 was among the few unions to defy McCarthy’s committee, and among labor’s most outspoken supporters of the civil rights movement. Martin Luther King, Jr. called District 65 “the conscience of the American labor movement” because of its consistent commitment to progressive causes. At the same time, District 65 itself was in the process of affiliating with the United Auto Workers (UAW). The eventual bankruptcy of District 65 in the mid-1990’s resulted in NOLSW becoming a direct part of the UAW as Local 2320. The UAW was one of the pioneers of the “wall-to-wall” unionism so central to LSSA. Among the UAW’s other claims to fame is the invention of the sit-down strike (Flint Michigan, 1948). The UAW’s concerns with autonomy and progressive politics led the union to withdraw from the AFL-CIO for several of that coalition’s most conservative years, but it later reaffiliated. Even more than District 65, the UAW proved from the beginning a devoted and invaluable ally in our political battles, including the fight to save Legal Services from defunding. The eventual bankruptcy of District 65 in the mid 1990’s—in large part due to the failure of membership numbers and employer contributions to keep pace with the cost of defined pension benefits for an aging membership—resulted in NOLSW becoming a direct part of the UAW as Local 2320. NOLSW was allowed to continue as a nationwide organization, one of only two UAW locals accorded that privilege. LSSA became the New York City “unit” of UAW Local 2320.

Fighting the Klan

In 1979-80, NOLSW’s second nationwide campaign was organized around the defense of North Mississippi Rural Legal Services. LSC was investigating the program for possible defunding at the instigation of local right-wing elements including the Klan. Hundreds of legal services workers from all over the country converged on Oxford and Tupelo Mississippi and marched down streets lined on either side with hooded KKK counterdemonstrators. The campaign culminated with a demonstration on Martin Luther King Day at the LSC headquarters. An NOLSW leaflet carried a caricature of LSC’s bow-tied president, Tom Ehrlich, in a Klan hood and demanded, “Which side are you on?” In the face of embarrassing publicity, LSC’s investigation ended with a whimper, and North Mississippi Rural Legal Services retained its funding. Years later, the program’s employees voted to join the union, 52-0.

The Reagan Years

In 1981, Reagan took office and within a few weeks mounted a “zero funding” campaign to eliminate Legal Services completely. NOLSW organized and fought a determined battle from the streets to the halls of Congress. We attended LSC hearings and helped coordinate a national Save Legal Services campaign. The wholehearted involvement of the UAW was decisive. Enough legislators were swayed to save Legal Services and to hand Reagan his first major political defeat since taking office. Throughout the 1980’s we continued to fight a series of battles against defunding and layoffs, limiting the damage and keeping legal services alive. At the same time though, our wages and benefits continued to erode, in part due to the lack of a seniority or “step” system.

In 1981, Reagan took office and within a few weeks mounted a “zero funding” campaign to eliminate Legal Services completely. NOLSW organized and fought a determined battle from the streets to the halls of Congress. We attended LSC hearings and helped coordinate a national Save Legal Services campaign. The wholehearted involvement of the UAW was decisive. Enough legislators were swayed to save Legal Services and to hand Reagan his first major political defeat since taking office. Throughout the 1980’s we continued to fight a series of battles against defunding and layoffs, limiting the damage and keeping legal services alive. At the same time though, our wages and benefits continued to erode, in part due to the lack of a seniority or “step” system.

Resisting Intrusive LSC Demands for Files on Employees

In January 1990, the federal Legal Services Corporation chair withheld grant checks to many LSC recipient agencies and threatened to defund our programs unless they agreed to report confidential information about staff members upon request to LSC, in violation of privacy laws and without being able to show a legitimate basis for their request. NOLSW and LSSA sent a delegation to Washington D.C. and lobbied the LSC Board in opposition to this policy change. In the end a compromise was reached whereby the programs were required to provide only basic employee information which included no employee evaluations, disciplinary records, or other confidential information.

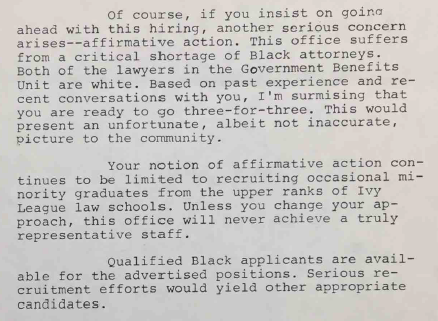

Fighting for Racially Diverse Hiring

While some offices such as Harlem Legal Services had a significant number of attorneys of color, the South Brooklyn Legal Services office had a poor track record of hiring attorneys of color, instead prioritizing elitist standards like graduation from Yale or Harvard Law School, which resulted in a predominantly white attorney group. The union demanded a seat on the hiring committee and fought to hire people of color. The attached excerpt is from a 1986 letter to SBLS Project Director Chip Gray, in a demand that SBLS hire more attorneys of color.

1991 Strike Wins Step System

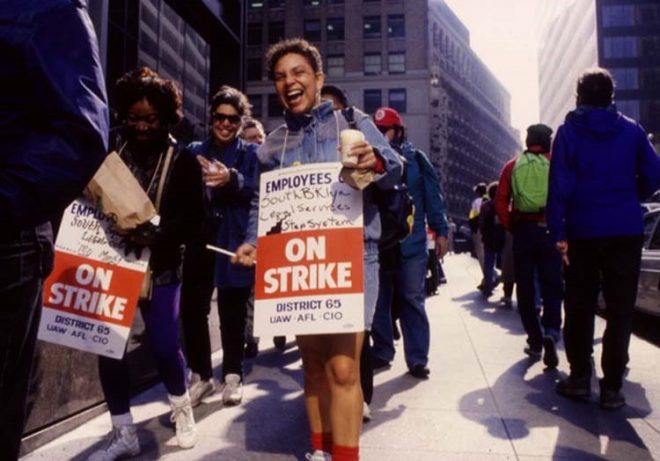

In 1991, with significant new funding available for the first time in years, LSSA members were determined to win back losses. At the start of contract negotiations, our union attorneys made 35% less than counterparts at the Legal Aid Society, and our legal workers made far less. Fred Lebron, who still works as a paralegal in LSNYC’s Queens program, told the Daily News that “you’ve got some people (support staff) who’ve been working here for 15 years and barely make $20,000.” The union demanded the creation of a step system with 45% pay increases for all job categories over the life of the two-year contract. This was intended to bring pay to levels comparable with other public service law jobs in the region. A report from the American Bar Association titled Standards for Providers of Civil Legal Services for the Poor had recently rebuked LSNY for its failure to raise salaries, concluding that management’s low pay policy represented “a very significant problem for the entire organization … that destabilized the programs, demoralizes the staff, and undermines the quality of legal work.” LSNY management responded to the union’s demand for equal percentage increases for all job categories with an offer of 15% increases for attorneys, 8.5% for paralegals and social workers, and 7.5% for all other legal workers. Union co-president Anita Miller responded, “We call for rejection of this effort to divide the union. We are committed to equal percentage raises for all union members.” Meanwhile, LSNY announced plans to reserve 34% of funds available for raises to raise management pay. New York Observer quoted co-president Deborah Stein as saying that without a pension, “a number of legal workers will be so poor that they will be eligible for our services under our own income guidelines. The idea that those who spend their lives serving the poor might then be eligible for the same services is pretty horrible.” After five months of contract negotiations without a serious offer from management, we voted to go on strike. The strike lasted for sixteen grueling weeks. Management negotiators slept or copied addresses at the negotiating table, pleaded ignorance of the issues, or went on vacation. They insisted on a mediator and then ignored her. They posted to hire scab replacement workers, provoking stern rebukes from twelve members of New York’s Congressional representatives and state legislators.

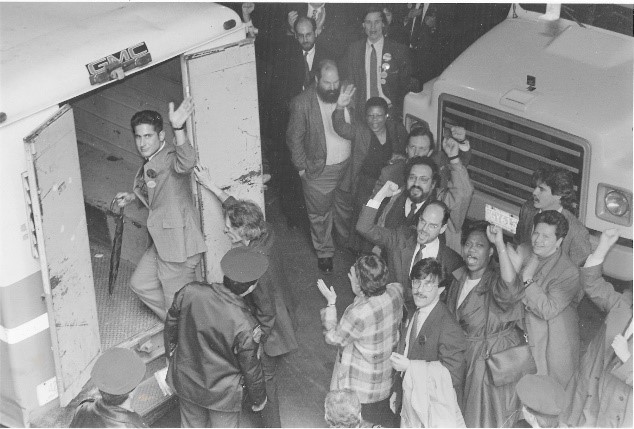

In 1991, with significant new funding available for the first time in years, LSSA members were determined to win back losses. At the start of contract negotiations, our union attorneys made 35% less than counterparts at the Legal Aid Society, and our legal workers made far less. Fred Lebron, who still works as a paralegal in LSNYC’s Queens program, told the Daily News that “you’ve got some people (support staff) who’ve been working here for 15 years and barely make $20,000.” The union demanded the creation of a step system with 45% pay increases for all job categories over the life of the two-year contract. This was intended to bring pay to levels comparable with other public service law jobs in the region. A report from the American Bar Association titled Standards for Providers of Civil Legal Services for the Poor had recently rebuked LSNY for its failure to raise salaries, concluding that management’s low pay policy represented “a very significant problem for the entire organization … that destabilized the programs, demoralizes the staff, and undermines the quality of legal work.” LSNY management responded to the union’s demand for equal percentage increases for all job categories with an offer of 15% increases for attorneys, 8.5% for paralegals and social workers, and 7.5% for all other legal workers. Union co-president Anita Miller responded, “We call for rejection of this effort to divide the union. We are committed to equal percentage raises for all union members.” Meanwhile, LSNY announced plans to reserve 34% of funds available for raises to raise management pay. New York Observer quoted co-president Deborah Stein as saying that without a pension, “a number of legal workers will be so poor that they will be eligible for our services under our own income guidelines. The idea that those who spend their lives serving the poor might then be eligible for the same services is pretty horrible.” After five months of contract negotiations without a serious offer from management, we voted to go on strike. The strike lasted for sixteen grueling weeks. Management negotiators slept or copied addresses at the negotiating table, pleaded ignorance of the issues, or went on vacation. They insisted on a mediator and then ignored her. They posted to hire scab replacement workers, provoking stern rebukes from twelve members of New York’s Congressional representatives and state legislators.  The union, with tremendous support from District 65 and the UAW, a substantial hardship fund, and strike benefits that carried the members until unemployment benefits kicked in, we organized support among elected officials and others, raised money and paid hardship benefits, fed the members daily, ran a free daycare center, faced up to armed scabs and goons, did civil disobedience, finally took over local offices, and much more. Twenty-three of our members were arrested for civil disobedience at a union action at the law firm Cleary, Gottlieb. Cleary partner Christopher Lunding was chair of the LSNY board, and was stalling settlement of the strike by refusing to hold board meetings. The photo at right shows arrested members walking into the NYPD paddy wagon. Charged with trespassing, all charges were ultimately dismissed when Cleary failed to prove that the union members were in Cleary’s offices without permission or reason. Our activist union also took over the MFY office on Avenue A, occupying the building to protest management’s plan to hire replacement workers.

The union, with tremendous support from District 65 and the UAW, a substantial hardship fund, and strike benefits that carried the members until unemployment benefits kicked in, we organized support among elected officials and others, raised money and paid hardship benefits, fed the members daily, ran a free daycare center, faced up to armed scabs and goons, did civil disobedience, finally took over local offices, and much more. Twenty-three of our members were arrested for civil disobedience at a union action at the law firm Cleary, Gottlieb. Cleary partner Christopher Lunding was chair of the LSNY board, and was stalling settlement of the strike by refusing to hold board meetings. The photo at right shows arrested members walking into the NYPD paddy wagon. Charged with trespassing, all charges were ultimately dismissed when Cleary failed to prove that the union members were in Cleary’s offices without permission or reason. Our activist union also took over the MFY office on Avenue A, occupying the building to protest management’s plan to hire replacement workers.  While on strike, LSSA strikers lobbied for homelessness prevention funding. Mayor Dinkins’ “Doomsday Budget” had slated anti-eviction funding to be cut. Camped out for two nights running, from the weekend into Monday, LSSA strikers lobbied City Hall and eventually succeeded in restoring the full $3 million in funding, and ensured that it remained in the final budget. By contract, management sent only one representative to lobby for the funds, who was there for less than an hour. After sixteen weeks, management finally caved, and we achieved enormous gains for the union. We created wage scales with step increases based on seniority, obtained unprecedented wage increases of 24.5% attorney raises and 17% legal worker raises over the life of the two-year contract, won a strong policy against sexual harassment, got retroactive pension contributions for our long-time members, and more.

While on strike, LSSA strikers lobbied for homelessness prevention funding. Mayor Dinkins’ “Doomsday Budget” had slated anti-eviction funding to be cut. Camped out for two nights running, from the weekend into Monday, LSSA strikers lobbied City Hall and eventually succeeded in restoring the full $3 million in funding, and ensured that it remained in the final budget. By contract, management sent only one representative to lobby for the funds, who was there for less than an hour. After sixteen weeks, management finally caved, and we achieved enormous gains for the union. We created wage scales with step increases based on seniority, obtained unprecedented wage increases of 24.5% attorney raises and 17% legal worker raises over the life of the two-year contract, won a strong policy against sexual harassment, got retroactive pension contributions for our long-time members, and more.

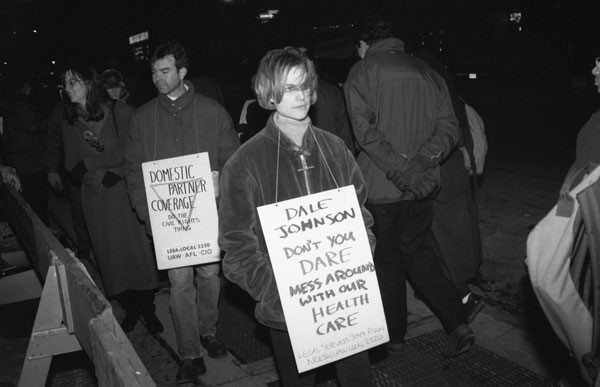

1993 Strike: No Givebacks, No Way!

In 1993, management went back to demanding givebacks, including an attempt to undo the new step system of wages and to significantly reduce health care benefits. Their insistence prompted another strike. The 1993 strike, which lasted for a month through the winter holidays, was not characterized by the level of organization and preparation or broad participation that marked the 1991 strike, and did not make comparable gains. However, it was important, necessary, and successful in holding the line against givebacks.  We also won domestic partner benefits for the first time. It was truly one of LSSA’s (and LSNY’s) shining moments when we negotiated one of the first labor contracts requiring health insurance coverage for same sex domestic partners of employees. At the time insurance companies in New York State would not offer such coverage because State law did not require it. Our contract actually read that LSNY would provide such coverage “when it became available.” LSSA and the UAW lobbied for a change in the regulations of the NYS Insurance Department and within months of settling the contract the domestic partners of our members had coverage.

We also won domestic partner benefits for the first time. It was truly one of LSSA’s (and LSNY’s) shining moments when we negotiated one of the first labor contracts requiring health insurance coverage for same sex domestic partners of employees. At the time insurance companies in New York State would not offer such coverage because State law did not require it. Our contract actually read that LSNY would provide such coverage “when it became available.” LSSA and the UAW lobbied for a change in the regulations of the NYS Insurance Department and within months of settling the contract the domestic partners of our members had coverage.

Increasing LSC Restrictions

The mid-nineties saw LSSA and NOLSW once again focused on fighting to maintain legal services for the poor. 1996 brought sweeping Republican control to the US Congress. Congress slashed LSC funding and imposed significant restrictions on the types of work that LSC-funded organizations could perform. Once again, we were confronted with a sustained political offensive in Congress to destroy the effectiveness of Legal Services. This time it was not just about reducing funding, but about imposing substantive restrictions on our work and on client eligibility, among other things setting up programs to jump or be pushed from LSC funding altogether. This is why LSC-funded organizations cannot bring class actions, and cannot represent many immigrants. Again, it was NOLSW that led the defense, and again, District 65 and the UAW were right there when we needed them.

Improving Working Conditions and Service Delivery

Through the 1990s and 2000s contract negotiations, we made a number of key improvements in our working conditions and the services we provide to clients. We fought to require caseload limitations to ensure professional responsibility on the part of case-handlers; private, enclosed workspaces for advocates to ensure confidentiality for clients; and training and supervision for staff to improve service quality. Too often, our union has had to fight for work conditions like these that LSNY management itself should have implemented for the benefit of the programs with no prodding from the union.

Fighting Mismanagement

There was another front to the battle for maintaining client services. LSSA found itself fighting misallocations of resources, inflated management costs, and arbitrary and discriminatory layoffs, particularly at Bronx Legal Services, Bedford Stuyvesant Legal Services, and Brooklyn Legal Services Corp. A. Literally most of the union staff was laid off from Bed Stuy before renewed union pressure and a catastrophic project evaluation from LSC finally ended the 13-year reign of Cherie Gaines, the tyrannical and self-serving project director who had driven the program into the ground. Brooklyn A suffered perennial financial crises that resulted in layoffs in the mid-nineties and culminated in 2001 with the loss of most union jobs but no management positions. Other programs throughout the city also suffered layoffs, or narrowly avoided them through staff sacrifices, in some programs repeatedly.

LSC Consolidation Pressure and the McBride Report

In the mid-to late 1990s, LSC began forcing the wholesale merger of legal services programs nationwide, and eventually ordered LSNY to start planning ways to consolidate and become more efficient. LSC’s 2000 “McBride Report” found that advocates and their programs projected a sense of inadequacy and isolation; that most LSNY programs limited their services to a narrow range of cases; and that failures in communication, coordination, administrative support, leadership and consistency of service quality had hindered LSNY’s programs from realizing their potential. The McBride Report suggested that a successful planning process would be geared toward giving staff the “sense of being part of a major, regional law firm with the size, resources, expertise and leadership to control its own destiny and shape the kind of advocacy it provides to clients and their communities.” Our union developed, and pressed LSNY to adopt, a restructuring plan that would integrate the system, improve the quality of services, enhance partnerships with community groups, and create accountability. LSNY refused meaningfully to address most of these concerns, and effectively dared LSC to impose a plan of its own. However, eventually LSNY did implement the current “membership corporation” structure allowing LSNY to force the firing of a project director as catastrophic as Bed-Stuy’s Cherie Gaines.

Programs Threaten to Break Away

Meanwhile, the opposite of planned integration of programs was occurring. Various local programs were working on their own plans to break away from LSNY, fragmenting the delivery of legal services in New York City even further, fragmenting our bargaining unit in the process, and leaving the LSNY-negotiated Collective Bargaining Unit behind them. LSSA responded to the threat by demanding, and winning in 2001, contract successor clauses to protect the union and its members in the case of disassociation.

MFY and Bronx Legal Services Disassociate

In 2002, two of the largest programs, Bronx Legal Services and MFY Legal Services disassociated from LSNY. Bronx Legal Services did not survive, and its entire staff was absorbed into a new integrated program, LSNY Bronx. Most of MFY’s most experienced staff were absorbed into the newly created LSNY Manhattan, with temporary management and no board, matters which LSNY never got around to addressing.

2003 MFY Strike

MFY kept the newer staff, who promptly organized their own sub-unit within LSSA. MFY began raiding other legal service programs’ funding and did its best to drive a wedge between its employees and the rest of LSSA, while setting out at the same time to bust the union at MFY with disastrous giveback demands and complete intransigence in bargaining. In an oft-quoted exchange, MFY project director Lynn Kelly gave staff five minutes to decide whether they would accept her offer, whereupon staff replied, “we don’t need five minutes.” The 2003 strike lasted nine weeks, largely in response to management’s demand that each member pay part of their own insurance premium. It was actively supported by the rest of LSSA, garnered widespread support, and ultimately produced a contract much closer to the union’s initial position than to management’s. More important than any particular provision of the contract was the dashing of Lynn Kelly’s hope that she could dictate to a smaller and less experienced bargaining unit.

MFY kept the newer staff, who promptly organized their own sub-unit within LSSA. MFY began raiding other legal service programs’ funding and did its best to drive a wedge between its employees and the rest of LSSA, while setting out at the same time to bust the union at MFY with disastrous giveback demands and complete intransigence in bargaining. In an oft-quoted exchange, MFY project director Lynn Kelly gave staff five minutes to decide whether they would accept her offer, whereupon staff replied, “we don’t need five minutes.” The 2003 strike lasted nine weeks, largely in response to management’s demand that each member pay part of their own insurance premium. It was actively supported by the rest of LSSA, garnered widespread support, and ultimately produced a contract much closer to the union’s initial position than to management’s. More important than any particular provision of the contract was the dashing of Lynn Kelly’s hope that she could dictate to a smaller and less experienced bargaining unit.

2003 LSNYC Contract Wins

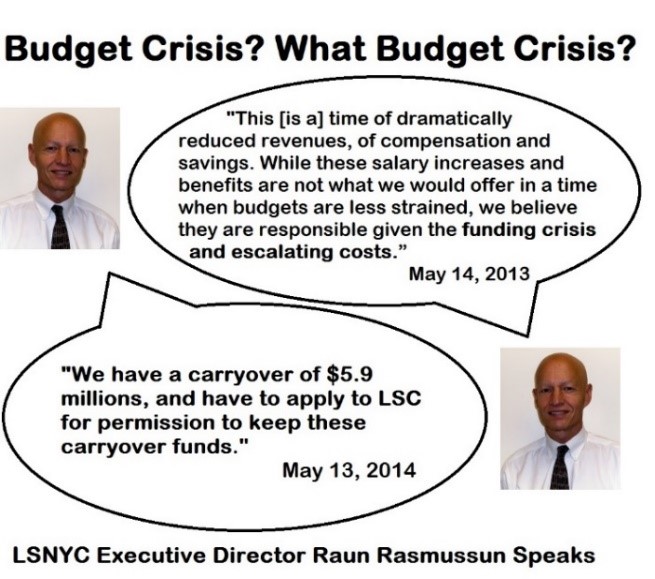

In 2003, LSNY management demanded that employees pay two percent of their salary toward the health insurance premium. We were ultimately able to resist a premium contribution, but our co-pays for both in-network doctor visits and prescription drugs both increased. For the next ten years, LSNY continued to demand in contract negotiation after contract negotiation that we contribute to our health insurance premiums, until they forced us to accept a 1% contribution in 2013 by falsely arguing that we were in a dire financial crisis.

In 2003, LSNY management demanded that employees pay two percent of their salary toward the health insurance premium. We were ultimately able to resist a premium contribution, but our co-pays for both in-network doctor visits and prescription drugs both increased. For the next ten years, LSNY continued to demand in contract negotiation after contract negotiation that we contribute to our health insurance premiums, until they forced us to accept a 1% contribution in 2013 by falsely arguing that we were in a dire financial crisis.  Our 2003 contract negotiation also saw salary improvements for senior staff who were not eligible for a step increase. LSNY agreed to pay them a two percent raise, not added to their base salary, in addition to the raises negotiated for the rest of the union members.

Our 2003 contract negotiation also saw salary improvements for senior staff who were not eligible for a step increase. LSNY agreed to pay them a two percent raise, not added to their base salary, in addition to the raises negotiated for the rest of the union members.

More Financial Mismanagement

The next round of crises came quickly, in 2004-2005. Bed Stuy and Queens were threatened with further staff cuts. A central cause of both crises was the fact that neither local management nor LSNY could accurately figure out until it was too late—and they certainly could not agree—how much money the programs actually had to spend. Only a combination of intensive union intervention and staff sacrifices averted complete disaster. In Queens, we succeeded in preventing the loss of 4 support staff at Queens only because each staff member sacrificed a portion of their own pay to bridge the budget gap. In Harlem, it was worse. Without meaningful oversight or accountability, the financial malfeasance of the mostly-no-show project director Shirley Traylor had extended to include hidden accounts and practices that led the state to demand funding returns and threaten indictment. Staffing levels plummeted, with negative effects on client services. LSNY, and the remnants of Harlem’s board, insisted on non-intervention for long months. A campaign of mounting pressure by the union, supported by community constituents, finally led to Traylor’s resignation. LSNY’s response, over strenuous union objection, was to force a consolidation of the so-far-solvent LSNY Manhattan with the bankrupt Harlem program, under that same remnant board that oversaw their program’s virtual demise—with no more direct oversight than before for Harlem, and less than before for LSNY Manhattan. The staffs of both programs, including most of the managers, argued passionately against such a consolidation pointing to each program’s deep connection to, and identity with, the communities they have served since the 1960’s. The staff and union were supported at the meeting by the Harlem Board and even by project director Peggy Earisman who advocated that a neighborhood-based model for the delivery of Legal Services worked best, was more responsive to the communities they served and their boards were more reflective of those communities.

Lobbying for LSNY Funding

2005 also brought another example of the many times that the union has gone to bat to save LSNYC funding. The Bush Administration announced plans to eliminate the Ryan White Care Act, which provided $1.6 million in funding to LSNYC to represent low-income persons living with HIV. As soon as LSSA was made aware of this threat to our funding and clients, we worked passionately with other NYC not-for-profits, NOLSW National President Ellen Wallace, and UAW Legislative Deputy Director Barbara Somson to fight to preserve the Ryan White Care Act. NOLSW also led the fight against cuts to LSC, which helped to prevent the Republican effort to cut LSC funding by 5%. On the City level, LSSA worked closely with our sister union, the Association of Legal Aid Attorneys, LSNY, and the Legal Aid Society in a united lobbying effort to protect our current funding and secure funding for new disability and unemployment programs, lobbying council members and testifying before City Council committees and borough delegations. We had a constant presence on City Hall steps during the budget negotiations, melting in the summer sun, to remind the council of the importance of our funding and make sure we could counter any threats to reduce or divert our funding. In the end, it paid off. Our new DAP/UI programs were funded at the full $2.5 million-dollar level to be shared equally between LSNY and Legal Aid. On the final day of budget negotiations, we stayed at City Hall until almost midnight to ensure that our funding was safe.

Protecting MFY Health Care

We won a number of significant victories in the MFY 2006 contract renewal, including 8.5% raises over the course of the three-year contract, and a $1000 signing bonus. MFY management also sought several unacceptable givebacks that the union successfully resisted. Health care benefits remained intact, as the team made it clear in the initial meeting that any health care givebacks would trigger a strike. The union team also stood firm against MFY demands that they be able to deny temporary employees union protection and benefits like health insurance for up to 12 months, and to limit the number of sick days employees could accumulate which would have been a disaster for long term employees struck with major illnesses.

Forcing LSNY to Address Disparate Tax Burden on Same-Sex Couples

Prior to same-sex marriage becoming legal in New York in 2011, LGBTQ staff members whose partners were on their health insurance had to pay an additional tax on the value of the health insurance coverage their partner received. This significant tax burden resulted in some staff members even having to give up health insurance coverage for their partners. In 2006, our union grieved this inequity and then raised it in bargaining, ultimately succeeding in persuading LSNY to reimburse same-sex couples for this tax burden, redressing this discrimination and recognizing the legitimacy of all of our families.

Fiscal, Administrative, and Tech Staff Join Union

The fiscal, administrative, and technology staff at Central, who had not been categorized as eligible for the union, gained union eligibility, rights, and benefits through the 2006 contract negotiations. This brought the accounting, accounts payable, payroll, and technology staff into the union and made us a true wall-to-wall union. We also expanded the step system, adding a new Step 30 for those with 30 or more years of experience.

Dysfunction in Bed-Stuy Management

There were serious problems for years in the Bed-Stuy program which the union brought to the LSNY Board’s attention time after time. In the mid-to-late 2000s, the Bed-Stuy program suffered through three successive project directors – Cherie Gaines, Camille Cook, and Victor Olds – who were unable to bring in funding, leading to increasing deficits they attempted to cure by laying off staff, and who created a poisonous environment without support or professional development for staff. Our union repeatedly called on the LSNYC Board to address the problems, including by terminating these project directors, dismissing the Bed-Stuy board, and consolidating the program into South Brooklyn Legal Services while maintaining the Bed-Stuy office location. We also filed grievances, brought them to arbitration, made complaints to the National Labor Relations Board, and sought the assistance of elected officials.

Brooklyn Consolidation Fails

From 2009 through 2012, then-executive director Andrew Scherer attempted to consolidate the Brooklyn programs into one corporation. This effort was opposed by the union, who argued that LSNY (by now rebranded as Legal Services NYC or LSNYC) should focus on replacing the Bed-Stuy board and project director, while retaining an independent neighborhood office answerable to the community. The union further demanded that LSNYC assure the union that union members would not be laid off, penalized, or involuntarily transferred if consolidation happened, and that LSNYC would not close neighborhood legal services offices. The consolidation attempt was ultimately defeated, in large part by community leaders in Bed-Stuy and in the Brooklyn Jewish community.

Manipulation of 2009 Buyouts

The backdrop to the 2009 LSNYC contract negotiations was the possibility of layoffs. In response, the union negotiated buyouts, reasoning that they would save money by inducing more senior staff, relatively safe from layoffs, to remove themselves and the costs of their higher salaries from the program. However, significant amounts were paid out to managers who, if their services were not needed, did not have to be induced at all. In the case of Chief of Operations Jeanne Perry, who was not being allowed to apply for the position that would replace hers, she was paid roughly $100,000 to go, and then was given an additional $100,000 to continue working with LSNYC as a consultant.

“Quality and Impact” Memo Targets Senior Staff

In 2009, LSNYC put forward an explosive new policy memo intended to provide guidance to borough Project Directors on how to improve the quality and impact of their legal work. Contained within it was a telling detail: it identified “personnel” as a priority focus area for 2010, and asked all project directors to consider “What personnel changes should be made?” It further asked them to identify “Who are my top priorities for change,” including for progressive discipline or retirement, and “what is my plan for taking on those changes?” The union immediately identified this directive as the game plan for an attack on senior staff. As predicted, what followed was an escalation in the targeting of our most senior (and thus highly paid) staff, disproportionately those in union leadership positions, for progressive discipline or termination.

Attack on the Legal Support Unit

In 2011, LSNYC undertook a massive reorganization of its Central office. It decided not to replace the outgoing Director of Communications, combined the Chief Financial Officer and Chief of Operations positions (a decision it regretted and reversed in 2016), and most importantly, undermined and then unilaterally eliminated the union positions in the Legal Support Unit by forcing out two senior staff out of seniority order and turning the Legal Support Unit into a ghost of its former self, staffed part time by managers.

2013 LSNYC Strike

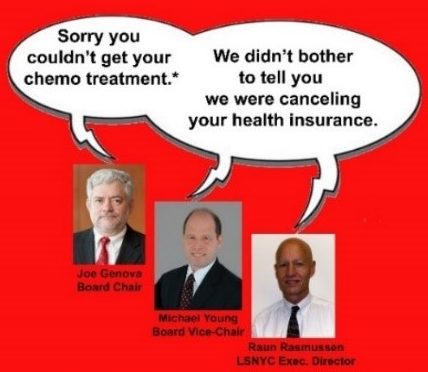

In 2013, LSNYC management proposed massive cutbacks to our healthcare and retirement benefits. The LSNYC workers struck for six weeks to fight those cuts, as well as to gain additional job security, gender identity and expression non-discrimination, and expanded parental leave. For the first time ever, LSNYC management terminated our health insurance when we went on strike, doing so without warning or proper notice. Though the UAW jumped in and was able to provide insurance coverage within a few days, the gap in coverage interrupted mental health treatment, access to medications, and for at least one family member, critical chemotherapy treatment. After six weeks on strike, LSNYC agreed to settle the strike after City Council Speaker Christine Quinn threatened to pull all of LSNYC’s city grants and contracts and award them to the Legal Aid Society, who promised to provide jobs for LSNYC’s union staff.

In 2013, LSNYC management proposed massive cutbacks to our healthcare and retirement benefits. The LSNYC workers struck for six weeks to fight those cuts, as well as to gain additional job security, gender identity and expression non-discrimination, and expanded parental leave. For the first time ever, LSNYC management terminated our health insurance when we went on strike, doing so without warning or proper notice. Though the UAW jumped in and was able to provide insurance coverage within a few days, the gap in coverage interrupted mental health treatment, access to medications, and for at least one family member, critical chemotherapy treatment. After six weeks on strike, LSNYC agreed to settle the strike after City Council Speaker Christine Quinn threatened to pull all of LSNYC’s city grants and contracts and award them to the Legal Aid Society, who promised to provide jobs for LSNYC’s union staff.  LSNYC justified the draconian cuts they demanded to health care and retirement by insisting they were in a financial crisis. They told us that LSNYC was facing a profound deficit, and that we all needed to make sacrifices. Shortly after the strike settled, LSNYC announced that they actually had an enormous surplus of almost $6 million in LSC funds. Rather than provide salary increases or bonuses to staff, or retract the 1% healthcare premium contribution they had forced us to accept, they instead gave only their managers raises, and still had to return $1.2 million to LSC.

LSNYC justified the draconian cuts they demanded to health care and retirement by insisting they were in a financial crisis. They told us that LSNYC was facing a profound deficit, and that we all needed to make sacrifices. Shortly after the strike settled, LSNYC announced that they actually had an enormous surplus of almost $6 million in LSC funds. Rather than provide salary increases or bonuses to staff, or retract the 1% healthcare premium contribution they had forced us to accept, they instead gave only their managers raises, and still had to return $1.2 million to LSC.

BKA Disassociates from LSNYC

Around the same time that LSNYC staff were on strike, the Brooklyn A program disassociated from the greater LSNYC program. Though LSNYC had repeatedly rescued the Brooklyn A program from its executive director’s financial mismanagement, the Brooklyn A management did not want its program to be consolidated with other Brooklyn offices into one Brooklyn program, and chose instead to become an independent organization. Brooklyn A then laid off all of its union staff, the vast majority of whom were re-hired by LSNYC.

2015 MFY Strike

In 2015, MFY workers went on strike in the midst of a bitterly cold winter. In developing the bargaining demands and strategy, the MFY shop focused on addressing the needs of women and people of color. MFY members Jota Borgmann & Brian Sullivan, in their 2016 CUNY Law Review article, Demanding a Race to the Top: The 2015 Strike Against MFY Legal Services in Context, write: “As a result…we placed particular significance on our demands for pay equity for administrative support staff. For the past decade, the vast majority of the administrative staff at MFY have been women of color.… [T]hey are also the lowest paid staff in the organization and endure the most challenging working conditions. A variety of factors affect support staff’s treatment within the organization as a whole and consequently, their engagement with the union. They include elitism, classism, racism, and practically speaking, greater oversight by and contact with managers that make support staff vulnerable to discipline.”  The union therefore sought a contract that justly compensated MFY’s lowest paid employees, added paid parental leave, and promoted retention of experienced staff, as the organization was seeing high levels of staff turnover. One particularly offensive management counter-offer was a modest parental leave offer which was contingent on staff agreeing to concessions that would undermine affirmative action hiring practices, something the union was unwilling to do. “We are fighting for a contract that works for our clients, that works for our lowest paid and most vulnerable members, and that raises the working standards of legal services workers,” said Jota Borgmann, a Senior Staff Attorney in MFY’s Disability and Aging Rights Project. “Management, on the other hand, wants to lead a race to the bottom. By doing so, they refuse to acknowledge that quality work comes from retaining experienced workers and that a social justice organization must ensure justice in its own workplace.” After over three weeks on strike in record-setting temperatures, we won a contract that ensures clients will be served by experienced staff, that creates a family-friendly workplace, and that respects the experience and dedication of our paralegals and administrative support staff. We demanded but did not achieve the hiring of additional support staff, the shortage of which is a worsening problem at MFY as it is at many shops citywide. This remains a key fight as we move ahead, to ensure that clients are served by a complete team of advocates.

The union therefore sought a contract that justly compensated MFY’s lowest paid employees, added paid parental leave, and promoted retention of experienced staff, as the organization was seeing high levels of staff turnover. One particularly offensive management counter-offer was a modest parental leave offer which was contingent on staff agreeing to concessions that would undermine affirmative action hiring practices, something the union was unwilling to do. “We are fighting for a contract that works for our clients, that works for our lowest paid and most vulnerable members, and that raises the working standards of legal services workers,” said Jota Borgmann, a Senior Staff Attorney in MFY’s Disability and Aging Rights Project. “Management, on the other hand, wants to lead a race to the bottom. By doing so, they refuse to acknowledge that quality work comes from retaining experienced workers and that a social justice organization must ensure justice in its own workplace.” After over three weeks on strike in record-setting temperatures, we won a contract that ensures clients will be served by experienced staff, that creates a family-friendly workplace, and that respects the experience and dedication of our paralegals and administrative support staff. We demanded but did not achieve the hiring of additional support staff, the shortage of which is a worsening problem at MFY as it is at many shops citywide. This remains a key fight as we move ahead, to ensure that clients are served by a complete team of advocates.

Improvements to Retirement Plan

In 2016, the union was instrumental in persuading LSNYC to change retirement providers by unearthing dishonest behavior by our Valic representatives and pressing LSNYC to seek other bids for our retirement contract. The new retirement provider, Prudential, provides our members with better investment options and lower fees. In subsequent years, we worked with Prudential and with members to implement auto-enrollment and auto-escalation, which will help make it easier to save for retirement. We continue to push both LSNYC and MFJ management to increase their contribution to our retirement accounts.

Ensuring New Staff are Placed on the Right Step

We learned in 2016 that since 2009 LSNYC management had often not placed new attorneys and social workers on the right salary step, and has not properly calculated anniversary dates (and their associated raises). We negotiated with management to get to a common understanding of how to interpret what the contract requires, and then did extensive training of our delegates so that delegates in each shop will be able to sit down with staff to make sure each union member’s salary and anniversary date is correct. This resulted in satisfying retro checks for many members.

Union Launches Program to Inform Law Students and High School Students about Unions

Many students, from high school to law school, aren’t aware of the benefits and protections of working for a unionized employer. Our union launched a program to attend career fairs to inform students about the value of finding a job that is unionized. Many law students we’ve met at the NYU and Fordham Public Interest Fairs have never considered whether an employer was unionized to be a factor in their job search, and are excited to learn what a positive impact it can have on their pay, benefits, working conditions, and ability to impact client services and the direction of their organization. We hand out a list of unionized employers across the country so that no matter what state their job search takes them to, they can be sure to send their application to unionized employers in that state. And when we meet with NYC high school students, we let them know about the great union jobs they can get serving their community while providing for themselves and their family.

Many students, from high school to law school, aren’t aware of the benefits and protections of working for a unionized employer. Our union launched a program to attend career fairs to inform students about the value of finding a job that is unionized. Many law students we’ve met at the NYU and Fordham Public Interest Fairs have never considered whether an employer was unionized to be a factor in their job search, and are excited to learn what a positive impact it can have on their pay, benefits, working conditions, and ability to impact client services and the direction of their organization. We hand out a list of unionized employers across the country so that no matter what state their job search takes them to, they can be sure to send their application to unionized employers in that state. And when we meet with NYC high school students, we let them know about the great union jobs they can get serving their community while providing for themselves and their family.

An Arbitration Win to Bring a New Position into the Union

We won a decisive victory in an arbitration against MFY to bring a newly-created position of “comptroller assistant” into the union. MFY’s management had insisted that it was a management position that wasn’t eligible to be in the union. The arbitrator strongly disagreed and ruled that the position should be in the union, rejecting MFY management’s attempt to frame program and admin positions as management positions. We were thrilled to be able to provide union benefits and protections to the staff member hired as the comptroller assistant. We then engaged in several months of protracted negotiation with the MFY executive director to determine what salary scale the comptroller assistant would be placed on.

Pushing Back Against the Trump Administration

With the election of Donald Trump, LSNYC again faced the prospect of a precipitous loss of our federal funding, when Trump vowed to eliminate the Legal Services Corporation. LSSA and the UAW lobbied jointly with LSNYC in Albany and on our own in Washington to protect LSC funding and plan for the possibility that the state would need to replace any loss of federal funding. Trump’s presidency brought an immediate attack against Muslims and immigrants with Trump’s imposition of a Muslim ban. Many of our members flocked immediately to the airports to represent and advocate for those affected. We sent a delegation of members to Texas for a week in December 2018 to represent immigrant women and children being held in a detention center as a result of Trump’s unconscionable targeting of immigrants seeking refuge and asylum. Our members were witness to unspeakable pain and returned with heart wrenching accounts of what our country is subjecting immigrants to. Together with our counterparts in the Association of Legal Aid Attorneys, UAW 2325, we organized simultaneous rallies in all five boroughs to protest Brett Kavanaugh’s nomination to the Supreme Court.

Trump’s presidency brought an immediate attack against Muslims and immigrants with Trump’s imposition of a Muslim ban. Many of our members flocked immediately to the airports to represent and advocate for those affected. We sent a delegation of members to Texas for a week in December 2018 to represent immigrant women and children being held in a detention center as a result of Trump’s unconscionable targeting of immigrants seeking refuge and asylum. Our members were witness to unspeakable pain and returned with heart wrenching accounts of what our country is subjecting immigrants to. Together with our counterparts in the Association of Legal Aid Attorneys, UAW 2325, we organized simultaneous rallies in all five boroughs to protest Brett Kavanaugh’s nomination to the Supreme Court.

Housing Representation Expands, and We Create Taskforce to Coordinate Unionized Housing Staff Across the City

The dramatic expansion of legal services in housing court has reshaped the landscape and had a huge impact on our work and services. Our union members have testified annually at the City’s Universal Access to Counsel hearing, as well as before New York State and City legislators. We created a taskforce of staff at unionized legal services offices across the City to address UAC issues including the underfunding of UAC by the City which forces our organizations to cut corners on hiring and staffing, overloading our members and hurting client services. When Covid hit, our citywide taskforce pivoted from UAC to focus on housing issues more expansively, from calling for an eviction moratorium and the cancelation of rent to opposing the reopening of housing court.

Union More Than Doubles in Size

From 2013 to 2020, our union membership more than doubled in size from less than 300 members to almost 600 members. This was due in large part to the expansion of funding for housing services which saw both of our employers hiring many new housing staff. In addition, we welcomed new members from BOOM!Health into our MFJ shop, adding a new office location in the Bronx to our MFJ shop. Our MFJ delegates worked attentively to welcome the Bronx members to the shop and bring everyone together as a cohesive whole, including excellent advocacy to address poor conditions at the old BOOM! office on Fordham Road.

Union Fights Back on Exploitation of Low-Wage Workers, Brings Miscategorized Temp Workers into the Union

LSNYC has a bad habit of regularly hiring workers through temp agencies, retaining their services for far longer than the six-week maximum allowed for in our contract, and conveniently failing to disclose use of the temp workers to the union as is required by our union contract. These time limits and notice requirements are intended to protect the union from being undermined and to protect vulnerable low-paid agency workers from exploitation. Despite that, LSNYC has regularly relied on low-wage workers (most of them people of color) from temporary agencies to fill long-term needs, while failing to honor its obligations to notify the union when it secures workers from temporary agencies. From receptionists at MFJ and Brooklyn Legal Services to maintenance workers and finance workers, through diligent effort and sometimes fortuitous luck, our union has discovered many of these temp workers and successfully brought them into the union, increasing their salary and in many cases securing back pay in addition to health insurance coverage.

Correcting Miscategorization of Legal Fellows

LSNYC also has a bad habit of miscategorizing legal fellows. In reviewing personnel forms we discovered that a number of our legal fellows, particularly those supervised at LSNYC Central, had been incorrectly categorized as temporary employees. Under section 3.1 of the CBA, with limited exceptions, any fellow hired for longer than 12 months should be hired as a permanent employee, and “in no case shall an employee be retained in temporary status for more than 18 months.” Since 2018 we have challenged the miscategorization of nine legal fellows and LSNYC has backed down, acknowledging that the legal fellows were all permanent employees, entitled to stay at LSNYC even after their fellowship ended.

Bronx Office Agrees to Reduce Use of “Split Titles” After Union Grievance

In 2018, we resolved an important grievance challenging the Bronx office’s overuse of combined lines, colloquially referred to as “split” or “slashed” titles, such as paralegal-slash-intake officer, or executive secretary-slash-intake officer. Although LSNYC CBA 14.3(E) states that “the combining of two lines will be done sparingly, and only if absolutely necessary,” 31% of the non-attorney, non-social worker positions in the Bronx had been split titles. Through the grievance process, we were able to remove split titles from a number of staff member’s titles while preserving the higher-paid title for each, and reduced the use of split titles to a little more than 10% of the legal worker staff in the Bronx program.

Fighting for Funding

Over the past few years, our union has been instrumental in securing or protecting crucial legal funding for our employers. Among other achievements, we helped to restore more than a half million dollars in funding through the Immigrant Opportunities, allowing both LSNYC and MFY to protect the jobs of staff immigration advocates who will continue providing vital services to immigrant communities around New York City, and we worked with a statewide coalition fighting for $20 million in funding to prevent foreclosures, a program known as Communities First.

Our Political Efforts

As a union, we work to support issues that affect our clients, communities, and fellow working people. In 2016 our delegates assembly voted to set political priorities of racial justice, workers’ rights and economic justice, anti-displacement and neighborhood preservation, and LGBTQ justice to guide our political efforts now and in the future. We started collaborations with city and national coalitions like the Fight for Fifteen and the Homes for All and Real Affordability for All campaigns. Every spring we sponsor a group of members to travel to Albany to meet with state senators and members of the state assembly on progressive issues affecting our clients and communities. To encourage more members to participate, we created a video showing what lobbying looks like. LSSA spearheaded the creation of the New York UAW’s 2019 New York State lobbying priorities, including strengthening affordable housing protections, reforming criminal justice, modernizing the unemployment assistance program, supporting the addition of an “X” gender marker on identity documents and drivers’ licenses, calling for the creation of a public bank, protecting immigrants, opposing Amazon HQ2, and more. As a part of the UAW, we interviewed and endorsed a number of progressive candidates for New York State office, and were the only union to endorse Tiffany Caban for Queens DA.

Fighting Racist and Oppressive Evaluations

Following reports from many staff of color of negative experiences going through the performance evaluation process, LSNYC’s Men of Color Caucus called on LSNYC management to suspend and reform the evaluation system. We formed a joint labor-management committee to address the pervasive and systemic issues with training and support as well as evaluations of and feedback for staff of color. This Performance Support Committee echoed the Men of Color Caucus and issued a recommendation that LSNYC’s current evaluation process should be immediately halted, and that supervisors should instead use the questions on the quarterly review forms to guide performance support conversations with staff. Our union’s Delegates Assembly voted unanimously to affirm this demand, stating “Any additional day that the current evaluation process remains in effect is another day that harm is inflicted on staff.” Following the Performance Support Committee’s recommendation, LSNYC management’s senior leadership team, agreed to immediately cease using the existing evaluation form and replace it with a more supportive and growth-centered conversation.

Health Care Improvements

We continue to fight to improve and expand our health care. In our 2018 round of bargaining, our LSNYC membership added reimbursement to staff who create families through adoption and surrogacy, and we were able to use the passage of New York State’s Paid Family Leave to increase LSNYC’s fully paid parental leave by four weeks, bringing leave for those who have been on staff for three or more years to 12 weeks of leave at full pay, and those who have been on staff for six months to 10 weeks of leave. In our 2021 round of bargaining with LSNYC, we increased parental leave further to 15 weeks for longer-time staff and 12 weeks for newer staff, and achieved equity in family creation by increasing reimbursements for those who create families through adoption and surrogacy to match reimbursements provided to those using infertility treatments.

When we learned that the LSNYC Cigna contract contained a blanket exclusion for any transgender-related hormones or surgery (this categorical exclusion has been illegal in New York State since 2014), we were able to get the Cigna contract updated and the categorical exclusion removed. We also persuaded LSNYC to extend fertility treatment reimbursement to all staff members, not just those on Cigna. In 2021, LSNYC agreed to create a reimbursement fund for TGNC staff to be reimbursed for gender affirming care that insurance companies refuse to cover.

Salary Scale Equity

In the 11th hour of our 2018 LSNYC contract negotiations, our union team made a shocking discovery: the structure of our salary scales was grossly inequitable, and those on the lower-paid salary scales received much smaller percentage increases as they moved from step to step than those on higher-paid salary scales. We spent the two years before the start of our next contract negotiations educating union and management on the problem and identifying its impact. Our analysis showed that these inequities are deeply racist: those staff on the lower-paid salary scales are disproportionately Latinx, while those on the higher-paid salary scales are disproportionately white and Asian. (We found that Black staff are equally represented on both higher-paid and lower-paid scales.)

In the 11th hour of our 2018 LSNYC contract negotiations, our union team made a shocking discovery: the structure of our salary scales was grossly inequitable, and those on the lower-paid salary scales received much smaller percentage increases as they moved from step to step than those on higher-paid salary scales. We spent the two years before the start of our next contract negotiations educating union and management on the problem and identifying its impact. Our analysis showed that these inequities are deeply racist: those staff on the lower-paid salary scales are disproportionately Latinx, while those on the higher-paid salary scales are disproportionately white and Asian. (We found that Black staff are equally represented on both higher-paid and lower-paid scales.)

In 2020 when we bargained a one-year contract in the midst of the COVID pandemic, we demanded that LSNYC cure these inequities and bring our salary scale in line with LSNYC’s commitment to racial, social, and economic justice, and to our principles of diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI). LSNYC refused to meaningfully engage with this demand for many months of bargaining, and remedying salary scale inequities remained a central demand for the 2021 round of bargaining.

When we returned to the bargaining table in 2021, we were able to achieve a fundamental change to the structure of salary scales that resulted in an average 10.8% raise in the first year of the contract for the primarily BIPOC staff on the six lowest paid pay scales. Staff on higher pay scales received a 2% increase in the first contract year. While more equity work remains to be done, this is a significant first step and structural change that LSSA will build on in future rounds of bargaining.

Covid Bargaining

The Covid pandemic emerged while our LSNYC members were in the midst of contract negotiations. Our team secured an agreement that “During the COVID-19 pandemic, given the uncertainty with regard to virus transmissibility and immunity and rapidly changing public health recommendations, the employer and the union shall meet upon demand of either party to negotiate and/or update policies for safeguarding the health of our staff, our families, and our clients.” Because of this agreement, management is largely prohibited from implementing anything that would impact our health and safety unless it is negotiated with our union. This agreement has allowed us to protect ourselves, our clients, and our families, while continuing to provide top-notch high-quality legal services.

Protecting Our Clients and Ourselves

We continue fighting for our members to ensure that LSNYC and MFY (now rebranded as Mobilization for Justice, or MFJ) remain excellent organizations where we can make careers providing quality services to our clients while supporting ourselves and our families. … and the rest is yet to come!